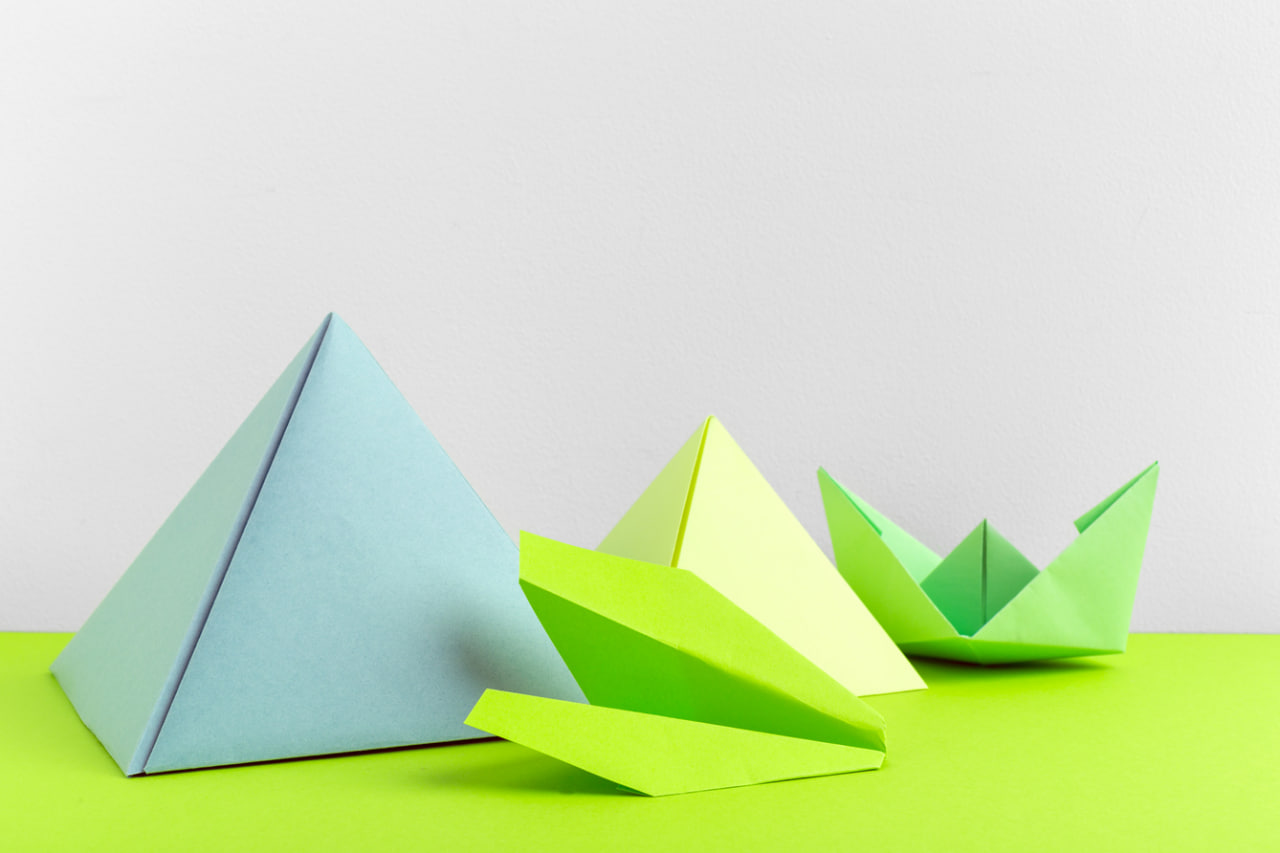

The History of Origami: From Ancient Folds to Modern Art

The Origins of Paper Folding

Origami, the art of paper folding, has a history as intricate as the folds it celebrates. Though the exact origins of origami are difficult to trace, its roots lie in multiple ancient cultures. Japan is most commonly associated with the practice, but paper folding traditions can also be found in China, Europe, and the Middle East. In ancient China, paper was invented during the Eastern Han Dynasty around 105 CE. Paper folding likely emerged not long after, originally used for ceremonial and religious purposes. Japanese origami, however, is where the craft evolved into the artistic discipline we recognize today.

Early Japanese Origami

By the 6th century, paper had made its way to Japan, where it quickly became a material for both religious rituals and artistic experimentation. The earliest documented origami was used in Shinto ceremonies, such as the folding of paper butterflies for weddings. These early models were simple, symbolic, and often paired with spiritual meanings. During the Heian period (794–1185), origami became more decorative, and the techniques started being passed down through generations. These folds were not merely decorative but embedded with layers of symbolism and cultural identity.

The Role of Origami in Education and Culture

By the Edo period (1603–1868), origami began to transition from sacred use to recreational practice. It became common among the general population, especially as paper became more accessible. Origami was increasingly viewed as both entertainment and a tool for teaching children patience, geometry, and fine motor skills. This period also saw the creation of many classic models, such as the crane, which later became a symbol of peace. Educational texts and illustrated guides began to circulate, allowing the tradition to spread more broadly and consistently.

The Influence of Western Folding Traditions

While origami was developing in Japan, Europe had its own paper folding practices. In Germany and Spain, folded paper was used in education and decoration. Spanish folding techniques, such as “papiroflexia,” shared similarities with Japanese origami but evolved independently. It wasn’t until the 19th and 20th centuries that the exchange of ideas between East and West began to merge these traditions. European folders began to adopt the Japanese term “origami” in recognition of the rich history and complexity found in Japanese paper folding techniques.

The Revolution of Modern Origami

The 20th century marked a major transformation in the art of origami, thanks in large part to individuals like Akira Yoshizawa. Often referred to as the father of modern origami, Yoshizawa introduced innovative techniques such as wet-folding, which allowed for more sculptural and expressive forms. He also developed a standard system of diagramming folds, which became the universal language of origami instruction. His work helped elevate origami from a folk craft to a legitimate artistic medium.

Origami in the Contemporary World

Today, origami is more than a craft—it is a global art form, a design principle, and even a tool in scientific research. Artists around the world use origami to explore themes of structure, impermanence, and creativity. Engineers and scientists use folding techniques to solve complex problems in areas like space exploration, architecture, and medical devices. From folding satellite solar panels to creating self-assembling robots, the principles of origami are shaping the future of technology.

The Cultural Significance of the Paper Crane

Among all origami forms, the crane holds a special place. According to Japanese legend, folding 1,000 paper cranes grants a wish or brings good fortune. This tradition gained international attention through the story of Sadako Sasaki, a young girl affected by the Hiroshima bombing who folded cranes in a wish for peace. Her legacy continues today through the global recognition of the crane as a symbol of hope and healing.

Origami as a Living Tradition

Origami continues to evolve. Artists push the boundaries of what can be achieved with a single sheet of paper, while schools and community centers use it as a tool for education and connection. Origami conventions, online tutorials, and social media platforms have made it easier than ever to share and learn from one another across borders. It is a testament to the adaptability and universal appeal of this timeless art form.